At first glance, “Yume Nikki” (which translates into English as “Dream Diary”) sounds like something out of an urban legend, or a weird horror story. It just kind of showed up for free download one day on the website of its enigmatic creator KIKIYAMA. There is no available information about KIKIYAMA’s identity. The game is entirely in Japanese, so if you want to play it you’ll probably have to install a fan-made translation patch (not that there’s really much text to translate). The game was created with the software RPG Maker 2003, which means that it looks like a Super Nintendo game. However, it is full of disturbing, violent, and just plain unnervingly odd images and themes. There are characters and events that only show up every now and then, ranging from 1-in-3 chance to 1-in-3600. While KIKIYAMA initially uploaded the game in 2004, they kept releasing new versions of it up until 2007. However, the current release is still listed as being “version 0.10.” After nine years, though, I think we can assume that there aren’t going to be any further updates.

You may have guessed that this isn’t going to be a normal sort of review. This is the first part of a series on “Yume Nikki” and its influence. In this part, I’m going to be looking closely at the original game and trying to pull it apart to see what makes it tick and why it was so influential.

The beauty of the story of “Yume Nikki” is that there isn’t one. Or rather, that the imagery hints at a story, but no explanation is ever given, thus the player is left to assemble a story for themselves. There are only three concrete points: 1) The main character (Madotsukai) is a hikikimori, a person (it often starts when they are young, like our main character) who completely withdraws themselves from society often being psychologically unable to leave their homes for years at a time. 2) The bulk of the game takes place entirely in Madotsukai’s dreams. 3) The ending (which I will not spoil here, but there will probably come a point while playing the game when you realize that it can only end one way). Past that, it’s entirely up to the player to try to string the dream images into something coherent. What is clear from the whole thing is that Madotsukai has suffered some sort of trauma. Once the player obtains a knife, they can use it to cut holes in some walls. These holes look like bleeding vaginas. There’s a bloody corpse in the road and the ability to turn your head into a traffic light. You can travel through something that looks like a concentration camp into an area that seems to be a combination of school and sewer where you will meet a ghost that removes your face. Not to mention all the hands and eyes, along with plenty of phallic and yonic imagery.

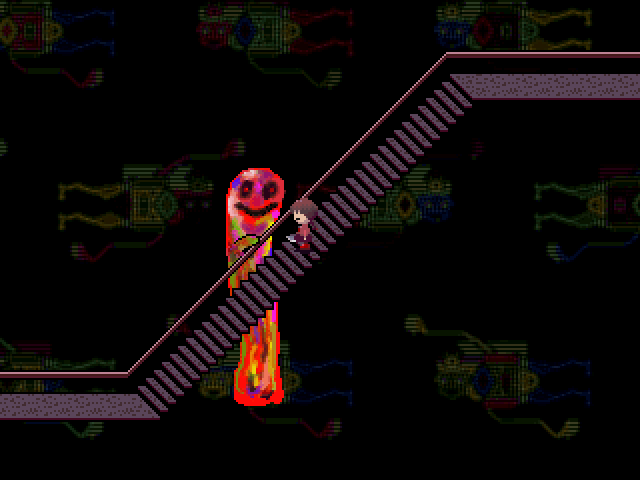

Then there’s the issue of the graphics. As I mentioned earlier, it looks like something that you would see on the Super Nintendo way back when in the mid 90s. However, as you may have guessed from the previous paragraph, the actual subject matter is very different (there were only 3 games even rated M on the SNES, Doom and two versions of Mortal Kombat 3). So you’ve got this very nostalgic look but its paired with exactly the sort of content that would never have made it past the ESRB back then. And I think that this is absolutely key to understanding why this game has earned its cult icon status. It evokes a sense of nostalgia at the same time as it corrupts it.

Then there’s the actual imagery. Like any good dream, “Yume Nikki” is full of strange imagery. There are areas like one that seem to be blank voids lit only by scattered candles or a spaceship that crashes on Mars. Most of the scenery tends to be more abstract, like the former, which makes the oddly “normal” parts of it feel very jarring. The same thing happens with the characters that lurk in Madotsukai’s dreams. There are weird creatures whose anatomy defies easy explanation, there are characters who seem to be human but with horrifically warped faces or bodies, but then there are a very few perfectly ordinary humans. Like with the scenery, the rarity of the ordinary humans makes them seem out of place. This is one of the truly brilliant things about the game. It manages to create a setting in which the normal is abnormal.

And of course, we have to talk about the game’s atmosphere. Madotsukai’s inner world is a reflection of the world in which she lives. That is to say, it is a terrifyingly lonely place. While awake, Madotsukai refuses to leave her studio apartment, except to go to the balcony. The only thing that she can do is sleep, play video games, or write in her diary. When she dreams, she is transported to these strange and fantastic worlds, but most of them are still either entirely or almost entirely devoid of life. There are vast spaces for the player to explore (and to finish the game you will have to thoroughly explore them), but so much of it is lifeless. That’s not to say that it’s empty, because it isn’t. But Madotsukai is so wrapped up in her own isolation that it extends into her dreams, and it is an isolation which the game expertly evokes in the player as well. That is really the core of the game. As it draws you in to explore its labyrinths, to solve the riddle of the dream imagery, it creates the same sense of isolation in the player that weighs so heavily on the main character.

At every turn, “Yume Nikki” seeks to do exactly the opposite of what a normal game would do. It gives you no clear story. It tries to make you feel isolated and lonely. It uses its nostalgic elements to actually further distance itself from the player and their lived experience. That is why it is a masterpiece. At the time it was created, there was nothing else out there like it. Sure, there had been a few RPG Maker horror games before (such as the original 90s version of “Corpse Party”), but nothing that approached horror in the same way that “Yume Nikki” did. It was all about creepy stories, exciting monsters, the excitement of fear, which is still the norm in mainstream horror. “Yume Nikki” is something truly different from that, in more ways that I could ever list here. “Yume Nikki” was revolutionary, a truly singular experience, so of course it attracted the cult audience that it did. And given that it was a clearly DIY sort of project, it was obvious that its followers would decide to make their own works, too.

Join me next week when we’ll take a look at the fan-made sequels.